One for the Ages

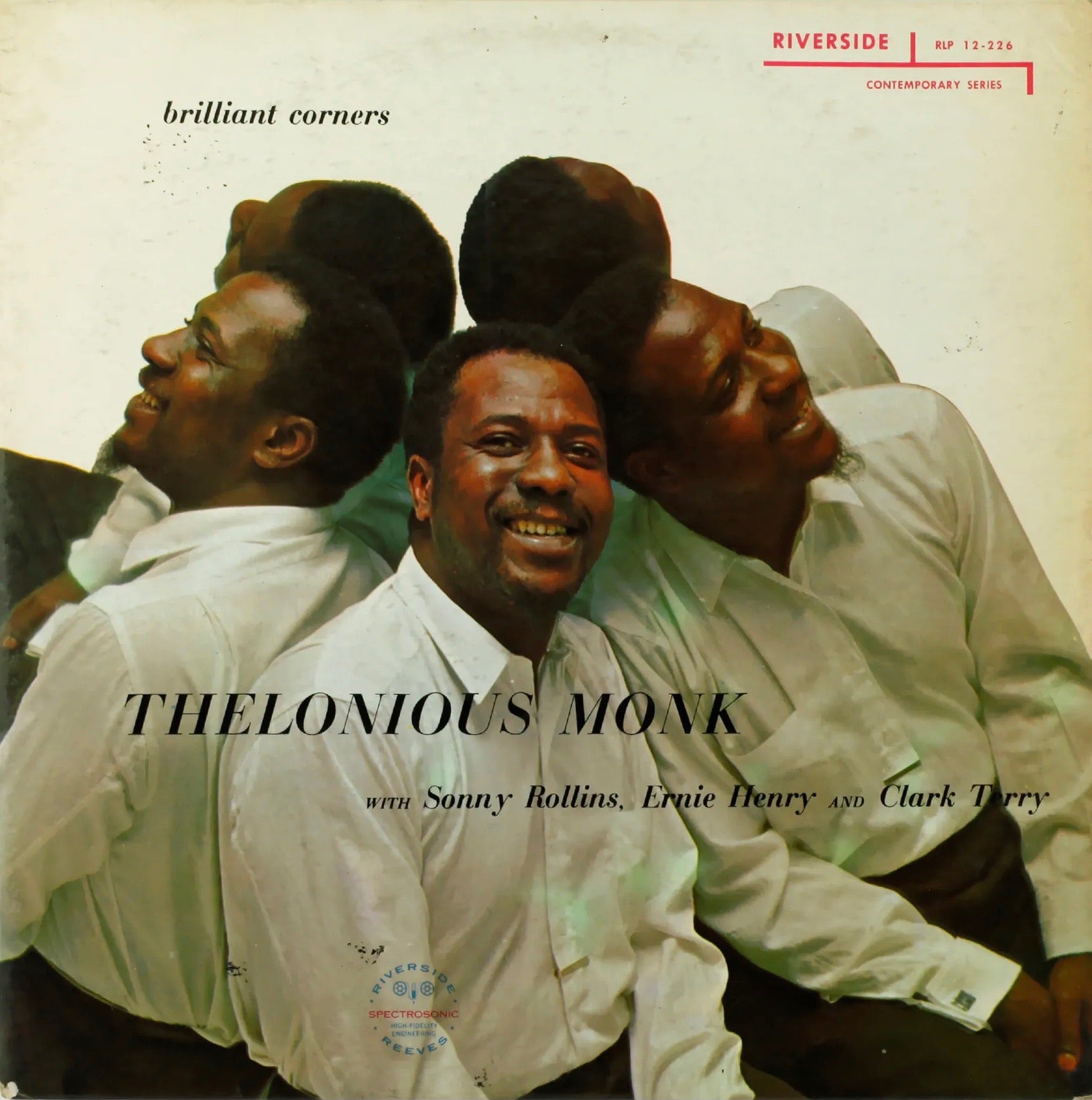

Drummer T.S. Monk, talks to DJ Pari (https://totallywiredradio.com/dj-pari/ ) about the making of Brilliant Corners 65 years ago, what it was like growing up as the son of a jazz legend, and his father’s legacy.

Brilliant Corners, your father’s third album for Riverside Records, is widely considered his masterpiece that put modern jazz on a different path. But critics didn’t really understand him at the time he made this album. Which historical truths does this recording hold 65 years after it was recorded?

This recording has profound meaning for me, on many levels, which I'll get into. But at that time in my father's career, he was extraordinarily focused on making his statement, and in my personal opinion, Brilliant Corners was probably one of the most revolutionary recordings in the history of jazz. You know, my father is often referred to as the High Priest of Be Bop, which was a convenient catch phrase for the media. But in reality, Thelonious is really the father of modern jazz, there's no question about that. In fact, his three primary devotees were Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Bud Powell. That's three guys that he personally mentored. I was there. I saw them all. And that includes Sonny Rollins, who was on the actual recording.

So he was really focused on making his statements as he saw them, regardless of the critics. My father once told me that, “don't believe the critics, because the same critic that says you are the most wonderful musician in the world on Tuesday might very well say you're the worst musician in the world on Thursday.” And so, you can't really go by the critics. But I would advise you off as a Monk fan, if you listen to Brilliant Corners – and I often tell this to students in university classes on Monk – I tell them, just listen to the top 10 or 20 recordings from those same years, all the best of jazz, and it will become very evident how different Monk was from of everyone else. And I mean from everyone else. Brilliant Corners was a total departure from what has been known as be bop at this time. Be bop was from a historical standpoint actually the transitional period or the bridge between modern jazz and the swing era. Thelonious really staked out a claim with Brilliant Corners and it's sort of remarkable to me that at the time, as odd as it was, the first time I ever saw Brilliant Corners on record, was not on an LP, but it was a 45 rpm recording that was in the jukeboxes across America. And I think one of the reasons that the company did that was because it was so edge cutting, relative to all the other things, and it was such a departure from what people had known.

You really can’t talk about Brilliant Corners without talking about his first album for Riverside, Thelonious Monk Plays Duke Ellington, which was remarkably different from his future direction ...

When Thelonious recorded that album, he was nervous as hell. Not about doing the album, but about what Duke would think of it. Because when you listen to that record, if you don't know Duke Ellington or you are completely unfamiliar with Duke Ellington's music, you would think those are all Monk compositions because Thelonious Monk found a way to put his stamp on Duke Ellington's music without compromising the compositional integrity of Duke Ellington's tunes. And Duke loved the album. In terms of my awareness, one of the biggest, most important albums that Thelonious ever did was that tribute to Duke Ellington.

Yet it didn’t include any original tunes, and neither did its follow-up, The Unique Thelonious Monk, although it was a superb artistic statement. So there was some criticism again, from the same critics, who said that the label denied Monk permission to record his own music. Did that bother him at all?

Well, you know, Thelonious was somewhat perturbed because the record company didn't quite know what to do with him. And so they made a conscious decision and they sat him and my mother down and essentially told him, “look, we ‘re gonna to have to sell you like a mad genius.” Which is really the birth of the whole concept that Thelonious was not of the tradition, that he was somewhat crazy. And Thelonious made a conscious decision, he needed to feed his family and he went along with that. And for the rest of his career that was a double-edged sword, because on the one hand he was told that he was a musical genius, and at the same time he was being told that he was inconsequential, that his music didn’t make any sense, that his piano technique was unorthodox.

But that’s really not true because he was classically trained and his style was deeply rooted in stride piano.

The idea that Thelonious wasn’t of the tradition was totally absurd. He was mentored by Jelly Roll Morton, Duke Ellington, Willie “The Lion” Smith and Art Tatum. If those are not actual pillars of the tradition, I don't know what else is. On top of that, Thelonious’ first piano teacher was actually a concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic who has often bragged that he had this little African American kid that was extraordinary at playing the likes of Chopin and Bach, and all these people. Thelonious didn't actually get into jazz until the woman that lived across the street from him on 63rd Street, who was a music and piano teacher, invited him over one day and showed him what jazz was all about.

To me that goes to the essence of genius, because genius generally is the culmination of a lot of hard work and a lot of study. Thelonious’s piano technique was actually his own idea, you know, that flat fingers approached, that percussive approach to the keyboard, and he broke up that constant back-and-forth rhythm from the left hand in classical music. When I was a kid, I was listening to Bird, and listening to Duke and Count Basie and Art Tatum and all these other musicians, and Daddy just sounded very, very different. In fact, I'll be very candid with you, by the time I was 16, I remember going to a couple of concerts with my father, which were exceptional concerts, but at the same time I kind of knew he was struggling, and I remember, to my own embarrassment today, I was saying to myself, why doesn't Daddy play like all those other piano players? Because they all sound the same, but they're all making money. But at that point I didn't quite get who my father was. In fact, I didn't discover who my father really was until I was 16. It wasn’t until I was 19 that I realized why he wasn't going in that direction, and it was because it wasn't him. He wasn’t hearing that, he was hearing something very, very different. And when people call him the High Priest of Be Bop, I say “Round Midnight” is not be bop. “Monk’s Mood” is not be bop. “Crepuscule with Nellie” is not be bop. And in subsequent years, tunes like “Monk’s Dream” and “Four in One” and “Trinkle Trinkle,” none of those tunes are be bop. Those tunes kicked be bop players’ asses.

When Monk got ready to record Brilliant Corners in the summer of 1956, he spent weeks holed up at the house of the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, working out the music. He put a significant effort into this recording, which shows that this album must have been very important to him.

Well, the first thing that Thelonious did when he was composing, he would work on a composition for weeks at a time, even months at a time. And in fact, I remember when he was writing a very strange tune called “Oska T.”, we were out at the baroness’ and he was working for weeks and weeks on this tune that was just these little phrases. It was no different with “Brilliant Corners.” He was playing it all day and reworking the harmonics, reworking the melody over and over, and over again. And the fact is that Max Roach and Sonny Rollins, and all these guys, were working musicians. They were doing their own gigs sometimes, or they were doing gigs with everybody. But yet they still had such a profound respect for Thelonious that regardless of what the critics had to say, they knew this guy was a genius. They knew this guy was brilliant. And so they actually asked to rehearse with him, when they might not have ordinarily acquiesced to be rehearsing. Because these were the kind of guys that were brilliant enough to walk into a session, they would play the tune and then go home. But they knew that with Thelonious’s music, it just wasn’t as simple because not only was there the technicality involved in playing this music, the difficulties, but there was Monk’s attitude, and you had to adjust to Monk’s attitude, which is something that I learned when I went on to perform with him at the later stages of his career. Playing Monk’s music requires an attitudinal adjustment. Because these artists understood that Monk was special, they said “we're going to have to work on this to get it.” And ultimately they got it right, but it was the result of a lot of hard work from Thelonious alone, and a lot of hard work from Thelonious and that particular ensemble to get that right and “Bemsha Swing” and “Pannonica” and all those compositions that were on that album, to get them straight.

So they had to work much harder than usual.

They had to really, really work at it because to this day, Monk’s music is always so easy on your ear, the melodies just sit out and always leave. They seem so simple and easy to understand, and yet when you actually need to frame them, whether you're talking to trumpet players or bass players and saxophone guitar players, they say “oh man, this is a Monk tune, I got, study this tune.” They all say that, I don’t care if you’re talking about Grant Green and Kenny Burrell, or George Benson and any of the great guitarists and piano players, they all know, when it’s about Monk, it requires a level of seriousness to get those harmonies proper because what Thelonious did harmonically, he was breaking the so-called classical rules, you know, parallel seconds and augmented extension, and chords, and all those kinds of things. Because Thelonious played the whole piano, the whole thing, and he also understood the various colors that you can get. Thelonious knew more music than all of them. Brilliant Corners really put everyone on notice that Monk was not going to follow the same pattern as piano players of that day, people like Red Garland, Wynton Kelly, and Oscar Peterson and Erroll Garner, and all these guys.

The music on Brilliant Corners is very difficult, and on the first day in the studio, they recorded “Pannonica” and "Ba-lue Bolivar Ba-lues-Are". They returned to the studio on October 15th, and the plan was originally to complete the album that day. But they struggled with the title track, and legend has it that things got heated between Thelonious, Oscar Pettiford and Ernie Henry, and they almost came to blows. How much of this story is true?

There wasn't going to be any fist fighting because everybody had a career to deal with. So nobody's going to punch anybody in the mouth. But there was consternation, because it was a very, very difficult piece of music, and Thelonious was very specific and precise as to the rhythmic placement and that sort of thing, all the technicalities in the music. I would suspect that it was a little more difficult. Thelonious was a one-take kind of dude. And most of those guys were one-take kind of cats, because we all believe as jazz musicians that after the first take generally things go downhill. So I think that that was a source of frustration, because they kept stopping and starting and stopping and starting, and Thelonious was just very, very specific about what he wanted that recording to be. That was just a general frustration that any artist feels in the recording studio when things aren't going exactly as you would like them to go. And so the guys get frustrated and want to take a break. And they’d say, “that last take, that was alright?” And Thelonious would say “no,” and the engineer would say “let’s do it again, fellas.” So that was a bit of a departure from what most of those guys were used to doing in the studio. But “Brilliant Corners” just wasn’t about “hit it, next tune.” Because Thelonious knew what he was doing and he was very specific, and I think he knew as much as anyone else knew that the composition was really, really different, and in order for it to be what he wanted it to be, it had to be exactly how he wanted it to be. And so he pushed, and ultimately the rest of the guys pushed on rhythm and came out with an absolutely brilliant recording, as brilliant as the title, “Brilliant Corners.”

As legend goes, things get exaggerated, and it's like playing telephone and the first guy says, “oh, he didn't like it.” And the next guy says “oh, he really, really didn't like it,” and by the time you get to the fifth guy, everybody hated it. So I think that's all that really was. But I know that to their dying day, everybody was really, really proud to be part of that recording, because that really was some cutting-edge stuff. And when you look back, you say, oh man, that's what we did? But it is very rare on the day of the recording that everyone is satisfied. That just goes along with the territory of being a cutting edge musician. You want everything to sound right, but you mostly want whatever you did to sound right. I think that's what the atmosphere was about. It was just guys trying to get it right and sometimes it can be very frustrating. Because remember, to all those guys in that session, that was the new shit, man. That was some different, very different stuff, man. There had to be a certain amount of frustration or trepidation. But it worked. To this day, I have never heard any musician say anything negative about Thelonious. Nothing.

The last studio session for Brilliant Corners was on the morning of December 7th. Clark Terry and Paul Chambers showed up on time, but Max Roach and Sonny Rollins were late. So that's when Monk recorded the solo piece “I Surrender, Dear” to make use of time. And when the other cats got to the studio, they cut the last tune, “Bemsha Swing.” You were six years young and your father brought you along for this session, so you were there. What are your memories from that day?

You know, it's funny, but I remember the microphones. It’s very weird, but I remember going to the studio and in those days they had these big, chrome RCA mics. And I remember the microphones themselves in the studio looked so fabulous. When you're six, you only see the obvious things. You don't really see the nuanced things about a studio. You see the tape recorder and the big wheels going around, and those microphones. I remember those microphones like it was yesterday. These great, big, giant RCA microphones. That was the standard of the day. I remember the room was very lit. It was an office-like atmosphere. It didn’t matter what the atmosphere of the room was, what mattered was the ensemble itself. And I remember them all being in this big room, and they were all together.

Max was sitting at his drum like a jet pilot. There was a lot of pearl and chrome, and then he had those two big kettle drums, the timpanis, which are brass, they look like copper. That scene of Max sitting at the drums is probably the most vivid image that I took away from that recording session, just looking at Max. From my perspective, it almost looked like Max Roach was the leader of the session and not Thelonious. And I think it's very interesting that the drummer Thelonious chose to play on that job was Max Roach. As a drummer myself, I know that we were not musicians until Max Roach actually changed the dynamics. Drummers went from being just simply living metronomes to actual musicians who played the song, and played the melody on the job. They were trying to do something very, very different. And when you listen to Max Roach on Brilliant Corners, he plays a solo at a tempo that you never ever, ever, to this day, hear a drummer play a solo at. And Max gave me a pair of his sticks at that recording.

And that day you decided to become a drummer yourself.

You know, every musician gets in a situation where, before you play an instrument, you see somebody playing the trumpet, or the saxophone, and somebody is playing the guitar, the bass. And you say to yourself, “oh man, I can do that.” And that day, at that Brilliant Corners recording session, when I watched Max Roach, I knew deep inside I was going to end up a drummer, because I could understand what he was doing. I didn't understand what my father was doing on the piano. I didn't understand what Clark, and Sonny Rollins were doing on those horns. But I understood what Max Roach was doing on drums and consequently, almost 10 years later, I became a drummer. But I didn't pick up the drums until I was 15 when I actually got the message that Max Roach was sending me about drums that day. But I fell in love with Max at that session. And I fell in love with the composition “Brilliant Corners” because it was just so different. I didn't understand what was going on, but it didn't sound like anybody else's music and it didn't sound like anybody else, you know, and the music was in the house all day.

Do you still have the sticks that Max gave you that day?

No, I don’t. But that’s ok, the sticks, that’s one thing. What I valued more than anything to this day is when I watched him play. And when I said to my father that I wanted to play the drums, he made two phone calls. He picks up the phone and he calls Art Blakey. I had never even seen my father make a phone call, because I was the official phone answerer, and my mother made all the phone calls. But he called up Art Blakey and said, “Hey Art, Toot wants to play the drums and I need some drums.” And about a week and a half later, I got some drums from Art Blakey. Then he calls Max Roach. And he says, “Max, you're the greatest drummer in the world and the kid wants to play the drums. So I'm sending him to your house.” And I go to Max’s house. I'm very grateful because I got to sit behind Art Blakey on many nights, and just watch him play. I would sit behind Max Roach and all these guys, at the Vanguard. I could go down there at any time, and I could just go sit. And if you know anything about the Village Vanguard, it's kind of V-shaped. If you sit all the way in the front on the side, you're right behind the drummer. And so I would always go get that seat, that very last seat near the stage, and from there I could watch Elvins Jones and Tony Williams, and all these guys play.

Your father wasn’t disappointed that you didn’t want to play piano?

My father gave me my freedom. He actually even released me from his shadow. There were people who were always asking me will I play the piano? There was a lot of pressure that was on me and my father said, “don't listen to those people. I don't care what you do, man. Just do your thing, the best you can do it. I love you.” And that removed that shadow that so many children of famous artists have over their heads because they feel obligated, and the world makes them feel obligated to follow in their father's Footsteps. And my father told me clearly that that was not necessary for him to love me. But he did not say one word, not one goddamn word to me about music for the next five years. And I went from practicing 15 minutes a day to two hours a day or four hours a day. And at one point, when I was 18 or 19, I was practicing eight to 10 hours a day. He was in the room right next to me, but he never said that this sounded good, or this sounded bad, or did you study. He never said any of that stuff and that was genius on his part, because he wanted to make sure that if I was going to take this rough road of being a jazz musician, I was going to do it because it was what I wanted to do, not what he wanted me to do.

After that day when he called Max Roach and Art Blakey, the next thing he ever said to me about music was almost six years later when he came into the house one day. I had finished high school, I was just practicing and trying to figure out what I was going to be. I didn't want to go to college. He just came into the house, and he looked at me, and he said: “You ready to play, man?” And I knew he wasn’t talking about basketball. And then he went on into his room. And maybe a week later, I was at my first gig on national television with him, and that's when my career with my father started. But I know in my heart – and I confirmed this with my mother – if he didn't think I could handle it, he would have never had me on the bandstand. He wouldn't have done that to me. So I'm thinking Daddy doesn’t give a shit about me and my drums, right? And my mother told me, she said, “Are you kidding? He listened to everything you were doing when you were practicing, and he knew when you were ready, even when you didn’t know you were ready.” And I am certainly grateful for that.

It seems that Thelonious Monk was quite the family man.

My father, aside from being one of the greatest musicians of all time, was a really good man and a good father. I can't say enough about how much I appreciate that because I've had the fortune or sometimes the misfortune of knowing the children of great jazz artists who had really no associations with their father. I have to tell you, Pari, I’ve had a very good childhood with Thelonious Monk. This guy about whom everybody said, “oh, he’s crazy, he don’t know this, and he’s not paying attention to that,” that's a bunch of bullshit. My father was totally into me and my sister. In fact, I've always concluded that he was more into my sister than he was into me, cuz she was four years younger than me, and she was Daddy’s little girl. He wrote “Little Rootie Tootie” for me, but he wrote “Boo Boo’s Birthday” and a tune called “Green Chimneys” for my sister. So I know he was crazy about my sister. And about “Green Chimneys,” when I was in private school the kids thought the song was about weed. But the private school that my sister went to was called Green Chimneys.

Didn’t he even give a free concert at your private school?

Right, so he comes to visit the school on a Sunday and takes me out to lunch and that kind of thing, and he says to me, “look man, I'm going to play a concert for your school. And once I do that, they’ll never be able to throw you out.” And he did the concert. And let me tell you, I was not the best student in the world. And I did a couple of things that were the kind of things that you’d get expelled for. But that school came up with a way to keep me on that campus, they just wouldn’t expel me. So he was right about that, too. He was a good cat. He really, really was a good cat, and a fun cat, and I can’t tell you how much I miss him. I’m 71 now, and Thelonious was gone at 63. Miles was gone at 64. So many of these cats didn’t have the chance to really live out their lives. That's why it was great to see Jimmy Heath, Hank Jones, McCoy Tyner live into their 80s and 90s and actually smell some of the roses, because Thelonious really didn’t get a chance to smell the roses. I can't even tell you what it was like in school when he was on the cover of Time magazine. Because today, if you wear a funny colored hat and you wear a mink suit, you can get on the cover of Time magazine. But at the time Thelonious was on the cover in 1964, that cover was reserved for the likes of John F. Kennedy. You really had to be an impactful individual, and I always loved the name of the article, because it said “Be Bop and Beyond.” And that’s who Thelonious was. They called him the High Priest of Be Bop, but he was so much more than that. I’m just very, very proud. It's been a lot of fun. I've had a really good run, and at the same time I came up with the name, T.S. Monk, because I wanted to figure out a way to detach from my father but stay connected. When I hit as an R&B artist, people said awful stuff about how I was a traitor, and “how can he do that to Thelonious Monk? He’s playing that dance music.” But my father was delighted that me and my sister had figured out a way to do something musically that has absolutely nothing to do with him. Because I can tell you, being Thelonious Monk Jr cracked the door open to the world of R&B. But beyond that, he couldn't do nothing for me, because he was of a different genre. But he was delighted, and once I knew he was cool with it, I didn't care what other people had to say. He was just a good guy and he always sent the right thing off to me. And I’m still having a ball.

What was Monk’s relationship with Miles Davis like? Historians tell us, they didn’t really get along.

There is a famous story of Miles, that Christmas where Miles told Thelonious to lay out (at the recording session for Miles’ 1957 album Bags’ Groove). But let me tell you something about Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis. I remember Miles coming to the door, and I was the official door answerer, and I opened the door and he said, “Tell Monk that Miles is here.” I’d go in the room and tell my father, “Miles says he's at the door.” And Thelonious just told me to open the door. And I open the door. On some days Miles would come in and Thelonious was wide awake, and they’d just just go to the piano and start going over “Round Midnight” or “Straight, No Chaser,” or anything like that. But there were other days when Miles would come in and my father would be laying down in the room and the arrogant, bellicose kiss-my-ass Miles Davis that everybody grew to know would come in, put his horn down next to the piano, sit on the piano stool and wait for Thelonious to get up. Sometimes my father would get up in 10 minutes, but at other times he wouldn’t get up for a half hour, and Miles would wait there for Thelonious. And Miles recorded “Round Midnight” 37 times.

The last time Thelonious and Miles were together, we were in the Baroness’s car, after Miles came down to hear Thelonious at the Vanguard. As we took Miles home, I was sitting in the front seat with the Baroness, and Thelonious and Miles were in the backseat talking, and Miles kept saying, “We got to record something together, man. Come on, we’ll make a whole bunch of money,” and he’d go on and on and on. And Thelonious would look at him as he often did and just grin, right? Because I don't think Thelonious was really up for doing that. But Thelonious didn't have any problem with any of those cats, particularly the younger musicians, like Miles, like Sonny Rollins. His peers were really Max (Roach) and Art (Blakey). Coltrane and those guys, like Bud Powell, were younger guys. They were over 10 or 12 years younger than Thelonious. And, you know, when you're in your thirties, if you are 35 and you talk to somebody who's 25, they are not your peers. And those guys acted like that, they would get mouthy. My father always said, “don’t be a scared motherfucker.” But I would watch these guys get so scared around my father, they didn’t know what to say, they didn’t know how to act. They would be very timid when they approached him, and he was pretty much a regular guy, but he had accrued so much respect that they didn't even know how to really talk to him.

But Monk had a very special relationship with Coltrane, despite their age difference, didn’t he? Their run together at the Five Sport Cafe in 1957 changed the trajectories of both of their careers.

He opened the door for Coltrane. Remember, when Coltrane left Miles, he was a junkie and he was basically a 27-years old has-been. He was done, he was cooked. And Thelonious said, “Come with me, man, and it’ll change everything for you.” I remember being in the apartment. We had the tiniest apartment, it was the size of a postage stamp and every day, this younger guy was coming over with his saxophone. And the piano was right outside me and my sister's bedroom. And I remember my father yelling and yelling at this young guy everyday, “come over,” and he's yelling at him. That preceded the stint at the Five Spot Cafe, which would put Coltrane back on the map as a giant, and Thelonious always encouraged him. I remember he was always encouraging him to do his own thing. I remember my father saying, “You don't need my help. You don't need nobody, man, do your thing.” And that's what Thelonious was all about.

So Coltrane joined Thelonious’s band, and I realized that Coltrane was the only one – whether you are talking about Sonny Rollins, and Johnny Griffin, or any of the tenor players that played with Monk – Coltrane was the only one that could play Thelonious’s runs on the piano on his saxophone. And when their collaboration was over – think about it – both of them adopted the quartet format as their staple. This is how they impacted each other, they both from that point on in their careers adopt the quartet as their staple. And Thelonious goes to get another young tenor player – although very different from Coltrane. Charlie Rouse had that new tenor sound. It wasn't the heavy Coleman Hawkins-Sonny Rollins-Ben Webster sound of the tenor, it was this vital sound, this more narrow, focused sound that Coltrane had. And Coltrane goes and gets this young piano player, McCoyTyner, who doesn’t give you what you got from Red Garland and Wynton Kelly. He's not playing patterns of rhythm, he's playing colors. And Coltrane goes and gets this young drummer, Elvin Jones, who is very similar – although he progressed – to (monk’s former drummer) Shadow Wilson, who was another drummer that played the swing rhythm, with an upbeat emphasis on the end of one instead of two. So they both ended up with those elements that they had discovered about each other together and incorporated that in both of their quartets. And the rest is history.

It's really amazing, because I didn't see that when I was younger, but as I became a more efficient and aware musician, I realized that Thelonious and Coltrane had profound influences on each other. And to this day, there's one tune called “Trinkle, Tinkle,” that nobody messes with since Coltrane messed with it. Tenor players just don’t mess with that tune, but Coltrane could play “Trinkle Tinkle,” and I mean crystal clear. And I know that Thelonious loved that, and when Coltrane died all of a sudden in 1967, my father flipped out. He flipped out when Bud (Powell) died, and he flipped out when Coltrane died, to the point where we had to hospitalize him. Coltrane was a profound influence on my father, and my father was a profound influence on John Coltrane. I feel very proud of the fact that I was able to produce the Monk and Coltrane At Carnegie Hall record which accomplished two things. First, it is now the second best selling jazz album, other than Kind of Blue by Miles Davis. And second, it actually verifies the impact Thelonious Monk had on John Coltrane, because people didn’t see it while it was happening, and even Coltrane never made any bones about it, saying “Oh man, what happened to me? I ran into Monk.” But nobody believed it, because you didn't see much writing about the impact of Monk and Coltrane, they were saying he had gone off in this new direction on his own. But it wasn't on his own, it was because Thelonious gave him the freedom and pushed him. And that's something that I personally witnessed, Thelonious pushing this young guy every day as they prepared to go into the Five Spot, pushing him every day. And I remember him saying things like “oh, yeah you can play two notes in time, you can play three notes in time, fuck the critics. Do your thing.” And all those things came out of Coltrane, and Miles and Coltrane did what they were supposed to do. When Miles started doing stuff like A Tribute to Jack Johnson and all that, he got criticized, I remember people calling him a traitor. Are you kidding? When Coltrane started doing stuff like “Kulu Se Mama '' and “A Love Supreme,” people were saying he was just fooling around. But I’ve never heard Thelonious say that because they were doing what they were supposed to do. They were pushing the envelope in new directions. I remember one night, my father came home. He was rambling on about Ornette Coleman. But he wasn't rambling on about what Coleman was playing, because Ornette was doing his own thing. He was rambling about the fact that on the tune he was playing the saxophone with a trumpet mouthpiece. But he did not have a problem with the direction that Ornette was going. Because there’s one thing that Thelonious respected more than anything else, it was doing your own thing. Whatever it is. Do your own thing and let the chips fall within that. I mean, that's why we all still run back to Lee Morgan, or back to Coltrane, and we run back to Clifford Brown, because these guys got it. They got it, you know Wayne Shorter, he got it. The greatest living composer we have in jazz is Wayne Shorter, hands down, man.

What about Dizzy Gillespie? He often took the credit for coming up with be bop while your father wasn’t recognized for his important role back then.

I used to get upset because Dizzy was very television friendly, and he would go on the Tonight Show and really suck up all the credit for be bop. And Thelonious just wasn’t that type of guy to toot his own horn all the time. So a lot of things that Thelonious pioneered, even down to the look, Dizzy got from him. One day he came home and he told my mother, “I saw these glasses in the store downtown, these dark sunglasses with these bamboo arms on them. If I wear these glasses, everybody will look at me.” And my mother was working two jobs, and Thelonious wasn’t working, but they took a couple of weeks’ salary. And they invested in that, and of course one of the most iconic pictures of Thelonious Monk is of him smoking with the piano reflecting in the bamboo shades .. He was very aware that he was in show business. So many things that Thelonious did were actually normal, but people just wanted to assign some eccentricities to him. If you see that picture outside Minton’s with Howard McGhee, he was wearing the beret and the ascot. Then Dizzy jumped on that. So Thelonious told my mother, “all these cats are trying to be just like me.” So that’s why he started changing hats. Because once cats started wearing the beret, and took that look, he would start changing his look every day. That’s why you see Monk in all these different hats, he thought if he changed hats all the time people wouldn’t be able to copy him. He also told me, “I don’t care if a cat comes in and copies what I play tonight, because I’m gonna play some different shit tomorrow night.” He was very aware of his ability to play things and structure things differently, everytime he sat down on the piano. Barry Harris told me, he said, “You never saw anybody like that. Monk could play 50 choruses, and make every single chorus slightly different than the one that preceded it.” And he said that is an extraordinary ability. Monk can do that, and Sonny Rollins and Coltrane could do that on the saxophone. That is pure genius, because jazz is actually hard to play. It's really difficult, and to become someone like that, you know, or like Miles. Nobody has ever made as many squeaks or mis-notes on the trumpet as Miles Davis on a recording, and nobody gives a shit. Because he was always reaching for something that he didn't know, that he wasn't quite sure about, and that's genius. What my father immersed me in was the philosophy of the music. Because these guys are philosophers, and Thelonious immersed me in the philosophy because he knew once I got the philosophy, I would be alright. And I got the philosophy. So I'm alright.

As a jazz DJ myself, I have to know, if your dad was still alive today, what would you think of young people dancing to his songs played by a DJ in a club?

I don't think it was necessarily weird for my father's generation, because you have to remember, my father and all those guys we’ve been talking about, they all grew up in probably the heyday of dance music. They all played dances, Thelonious came up playing dances. Max Roach used to tell me about how he used to drag his drums to the subway, to play dances, and in those days it was like 3,000 people dancing. People were dancing all night, and so they always felt that they were dance musicians. The Cotton Club was about dancers! People only stopped dancing to this music when they brought the music out of Harlem downtown and sort of wanted to, for lack of a better term, civilize it. So they came up with a dance tax, which made all the clubs close the dance floors, and the next thing you know people were sitting down at the table, eating dinner listening to jazz. So I think that people of my father's generation would say they are glad that people got hip again.

People used to think Thelonious was crazy because he used to get up from the piano and dance while the rhythm section played, which was something else that he revolutionized, because piano players never got up from the piano. Are you kidding? And all over sudden Monk got up from the piano and he started spinning in circles. And people thought that, oh, he's really nuts, cuz he likes the music so much, he’s spinning in circles. But what they did not know was that Thelonious was the descendant of slaves that came from Africa. And that little spinning step that Thelonious did was actually a variation of the most ancient of African dance steps. But people didn’t know about the history of African Americans, so they just thought he’s eccentric, he's just spinning in circles cuz he's crazy. But he was doing a dance that has been passed down by generations of African slaves for hundreds of years.

Why didn’t Monk take it upon himself and combat those rumors about his eccentricity and weirdness?

Because by the time the critics really wanted to talk to my father, he didn't want to talk to them. And so you get this history that Monk didn't like to talk, but they brutalized him for the first 35 years of his career, so he didn’t want to talk to no critics. But I feel that because he was such a good father, because I actually lived with him, he taught me how to treat girls, he took me everywhere with him, I see it as my duty to tell people what this guy was really like. Because if you read about Monk, you’d think that Monk was just this strange dude, he didn’t talk to anybody, all that bullshit. And it’s not the case at all. He loved life, he was a fun guy, he had some emotional issues that at the time that the psychiatric community was not able to deal with. Of course today, manic depression and schizophrenia, that’s all treatable today, but it wasn’t at his time. And so that's unfortunate. But you know, a lot of that shit that goes to genius. When you talk to people who really knew Picasso or really knew Michelangelo, they’d say, “oh, yea, he was a weird motherfucker, man.” That goes along with the genius, because people like Thelonious are not regular. Thelonious was very politically aware. When he was young he did fundraising for the NAACP, he was very active and very, very engaged. This actually paints a completely different picture. And then the guy that we know as Thelonious Monk actually makes more sense. When you find out what this guy was really about and what was really on his mind.

And he was a threat, too. You probably watched that new story of Billie Holiday that was on Netflix (The United States vs. Billie Holiday), about how the FBI used to criminalize the jazz community and the entire African American community through the use of cannabis, which they are now making legal everywhere. They were keeping files of Billie Holiday and Martin Luther King Jr., and all these people. And I said to myself, he's my father. He's a very large, very independent African American male back in the 40s, 50s and 60s. He kind of fits the profile of the kind of people that they were investigating all the time. And it's very weird to me that when he got busted for marijuana in Delaware, I always thought it was odd that the cops didn’t beat him on his head. They were beating Black folks with billy clubs over the head all the time, they did it to Bud Powell, and he was never the same after that, but the cops in Delaware did not beat Thelonious in the head. They beat his hands. And that told me they knew who he was. I did my research and called a couple of friends who had connections and found out that the FBI had a file on Thelonious Monk. Because you got this Black man, who's running around with the richest white woman in the world (the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter). If that's not the reason from a J. Edgar Hoover perspective to investigate him, what better reason could you have? The FBI had a file on Thelonious just like they had a file on Malcolm X and so many great Black artists, like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday. It's a crazy world, man.

Well, I’m really glad that you’re sharing all these stories, because it helps those of us who are too young to have met him, understand the man behind the music.

I have to tell you that, I appreciate you not only getting some of the facts that I'm aware of, but just letting me give you all this subsequent information that sort of rounds the picture out about Thelonious. Because like I said, I feel like I have to speak for him, because by the time they wanted him to speak for himself, he didn't want to speak. I’m a very great advocate of my father, because he took all the elements of be bop, he took all the same 12 notes and he came up essentially with a new vocabulary, both melodically, and harmonically. And the latter is probably the more important of the two because what Thelonious did harmonically kicked the door wide open. You have to remember that at the time, the critics said he's playing the wrong notes and he swings the wrong chords. And I find it very fascinating today that I can’t find any of those critics.

And I recall when we had started this Monk Institute of Jazz in the late 1980s, Leonard Feather called up the office and said, “I want to be a part of the institute,” and I was livid. I called my mother and I said, “Ma, this motherfucker wants to be part of the Monk Institute.” I remember the only violent act I ever recall my father doing was when he ran into Leonard Feather outside of the Musicians Union one day and actually grabbed him by his collar and threw him against the wall. And he said to him, “look, man, I'm trying to feed my family. I got two kids home and if you don't like the way I play, just don't write anything about me. Write about all the guys you love, but get off of my ass.” So when I told my mother that I was upset about Leonard Feather’s request, you know what she said to me? She said, “Toots, you have to understand that Leonard Feather was part of a crowd of millions of people who didn’t get Thelonious in the beginning. But he got him eventually, so you can't be angry with him. Unless you want to be angry with the millions of people who did not understand your father when he first came out.” And I took that to heart, and Leonard Feather became part of the Monk Institute.

And I'm proud of the fact that I was able to change, and I was able to get a different perspective and understand that just because they are critics doesn't mean they always get it. But at the time, it was so different, and Thelonious was so different from all the other piano players. And I think one of the things that perhaps has made you enjoy Thelonious’ music and made millions of his fans worldwide enjoy the music is the fact that as the critics came down on Thelonious harder and harder, he remained steadfast. And I’m very proud of that because I think that's one of the reasons for when I was six and seven years old, people used to say to me, “your father is gonna be bigger 50 years from now than he is today.” I really didn’t believe it, but here we are, 65 years later, and his composition “Round Midnight” is the most recorded tune in jazz history and he is second now only to Duke Ellington as the most recorded artist and composer in the history of jazz.

So, you know, my father used to say, “I'm right, they're wrong,” and even I talked that up to some kind of magic, but you know what? He was right, and they were wrong.