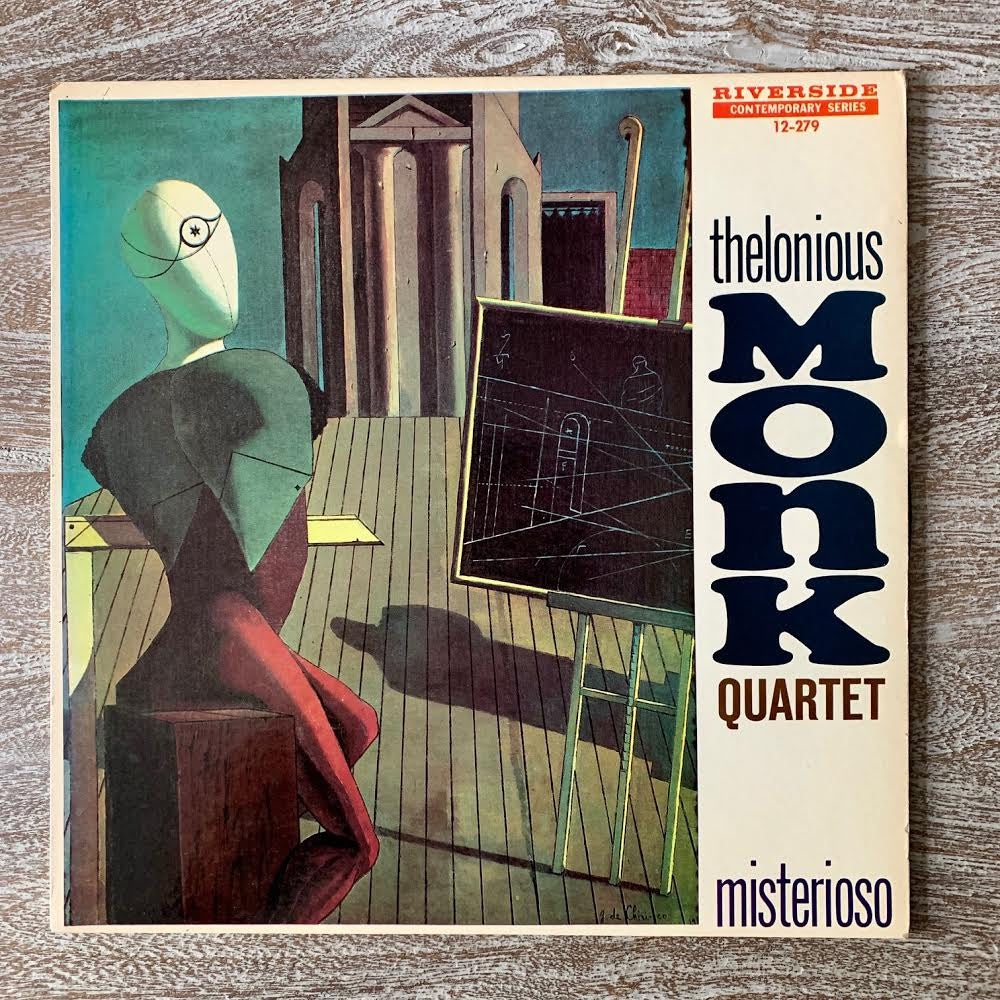

The Making of Misterioso

By DJ Pari

It’s shortly after 7 p.m. on Aug. 7, 1958, a hot, humid summer night in New York City. Upon walking through the doors of the Five Spot Café, a popular storefront bar in the Bowery neighborhood between the East and West Village, you find yourself in a crowded, dark den shrouded in a haze of cigarette smoke, a small, but rewardingly intimate setting, the atmosphere tinged with the bite of a gin cocktail. The walls are plastered with mirrors, photos and posters, curtains, and tapestries, saw dust covers the floor, but there isn’t a stage, only some slightly raised flooring at the end of the room, barely wide enough to fit a drum kit and an old upright piano.

Behind it sits a towering figure, immersed in thought, backlit clouds of smoke wafting around him. It’s Monk, in deep concentration, oblivious to the faint chink of cutlery and quiet conversation and laughter still filling the air. He places his long, slender fingers on the keys, preparing to hit that first note, as his sidemen watch in anticipation. Just a few steps from the bandstand, Orrin Keepnews, record producer and owner of Riverside Records, and engineer Ray Fowler sit behind the controls of a two-track tape recorder. Keepnews is here to record Monk’s sets to be released later that year on two albums; Thelonious in Action and Misterioso. Because of when, where and how this music was recorded, and due to Monk’s selection of musicians to accompany him, the latter set today is considered one of the pianist’s most intriguing albums and the first successful attempt at capturing his live performances on tape. It is the perfect storm.

To fully understand the magic of Misterioso, let’s step back for a minute and examine the historical context, beginning with the venue, which is as much a star on this album as the artist whose name graces the cover. The Five Spot Café, a small jazz joint with a capacity of 75 seated, was opened by Joe and Iggy Termini, two brothers with deep family roots in the Bowery, in late August 1956. Their bar quickly became a favorite hangout for many writers and beat poets, including Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, and abstract expressionist painters like Frank Kline, Larry Rivers and Willem de Kooning. The patrons were united in their attraction to the creative consolidation of jazz in the 1950s, as propagated by the genre’s progressive modernists, most notably Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke, Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk.

But Monk would have to wait almost an entire year for his Five Spot debut (the honor of the club’s first long-term engagement was bestowed on pianist Cecil Taylor), until the long suspension of his cabaret card, which he had lost after a drug bust on Bud Powell several years earlier resulting in a drawn out seclusion from public performing that his wife Nellie called the un-years, had been resolved. With the help of the Termini brothers, his card was returned, and Monk took up his first six-months residency, beginning July 4, 1957, working six nights a week, four sets a night. At first, Monk performed with Cecil Payne and Duke Jordan’s group, but after two weeks he brought in his own quartet that featured John Coltrane on tenor sax, Wilbur Ware on bass and Shadow Wilson on drums. Unfortunately, there are no recordings documenting this first stint at the Five Spot; the artists’ various contractual obligations prevented such documentation.

However, Monk returned to the Five Spot in the following year, in his pocket his contract for a second engagement, lasting eight weeks. Excited with the pianist’s return, the Termini brothers hailed the Five Spot as the “home of Thelonious Monk.” And this time, the pianist took a different group, substituting Ware with 21-year old bassist Ahmed Abdul-Malik and Wilson with Roy Haynes, a former drummer in Charlie Parker’s quintet. The most noticeable change was the replacement of Coltrane by Chicago native Johnny Griffin, who had just finished a brief stint with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. Monk’s decision to hire Griffin proved controversial at first. When the group kicked off their residency on June 12, 1958, the saxophonist came unprepared. Unfamiliar with Monk’s repertoire, he struggled to solo over the pianist’s dissonant, asymmetrical comping and the sonic complexity of his compositions, essentially trying to learn the tunes and work through their changes on the bandstand. Monk, graciously sensitive to his sideman’s throes, often left to the bar for a drink or danced among the audience, allowing Griffin more space to play (something that he had done for Coltrane as well in the previous year).

Keepnews’ first pursuit to record the quartet during two sets at the Five Sport on July 9 was unsatisfactory, and Monk did not approve of a release (although some of the material would eventually emerge after his death). At a second attempt a month later, during an evening show on August 7 before a capacity crowd, the group was nearing the end of the residency, really playing together, communicating with telepathic powers. And this time, Keepnews struck gold.

Kicking off the set is the buoyant mid-tempo swinger “Nutty;” the group takes the audience into familiar territory. Monk first cut the tune during a recording session for Prestige in 1954, making it up on the spot, and it had become an often-played staple in his repertoire. After Monk’s introduction of the theme, Griffin comes in, stating it again in unison with the pianist. Then Griffin’s solo ensues, and it’s clear that the saxophonist has overcome his battle with the challenging intricacies of Monk’s compositions, his notes floating freely and confidently, in double-time, dancing on top of the pianist’s abstract chords. Monk’s own solo, as so often, defies most rules of logical chord construction, playing expressively yet deliberate, until Griffin picks up the theme once again.

“Blues Five Spot,” the only new tune on Misterioso, is a bubbly ballad based on an unaccompanied original called “Dreamland” that Monk rarely performed, renamed here for the purpose of paying tribute to the host venue. A successful exercise in unmasked humor on the bandstand, Monk and Griffin’s solos are exceptional, despite the saxophonist’s occasional tendencies to allow his technical prowess to outshine his creative wit, with Abdul-Malik and Haynes reliably grooving deep in the tune’s undercurrent.

What comes next is one of the album’s highlights, a first crescendo before the big detonation. The nine-minute workout of “Let’s Cool One,” first recorded for Blue Note in 1952 and a favorite that would reappear in countless carnations throughout Monk’s career, marks Griffin’s grand moment on Misterioso. Monk’s laid-back stating of the familiar melody, eventually joined by Griffin, barely pierces through the chatter from the audience, evidence of their utter unpreparedness for what comes next. Ready to take the spotlight, Griffin shouts: “I got it, I got it,” prompting Monk to lay out, which the saxophonist takes as his cue to send out a flurry of notes before launching into a ferocious sermon, squeaking and wailing and attacking the theme, exploring its melodic possibilities while Monk, sitting quietly, likely wiping his face with one of Nellie’s huge, sweat-soaked handmade handkerchiefs, watches in awe as Griffin ascends to the summit. When he hits the climax, Haynes’ famous snap-crackle snaps the mesmerized listeners out of their hypnosis, the small room fills with thunderous applause and shouts of cheer as Monk, smiling knowingly, brings the tune home, a perfect ending for side A.

Upon flipping the record, boom, “In Walked Bud,” another favorite and the most thrilling 11 minutes on Misterioso. In this tribute to Monk’s understudy Bud Powell, based on the chord progression of Irving Berlin's “Blue Skies,” everyone gets to shine. Monk sets up the mood with his 8-bar introduction of the theme, Griffin plays quirky and full of confidence, Abdul-Malik solos, with a groove locked air tight, Haynes demonstrates his impeccable timing and lively touch. And Monk, well, he is trying to out-Monk himself, swinging hard, reveling in his trademark tonal dissonance.

Next up, “Just a Gigolo,” the only song on this album not composed by Monk, which may explain why he keeps it short and sweet, just under three minutes, unaccompanied. Use it to catch your breath, have a sip of wine, get ready for the encore. The closing track lends the album its name, one of Monk’s earliest compositions, dating back to his first Blue Note sessions in 1948. Here, the quartet picks up the pace and turns the tune inside out, over 11 minutes, brevity isn’t a thing yet. In his liner notes, Keepnews muses that Misterioso is more than just the name of a tune, but an “extremely Monk-like song title, evoking by its mild play on words (linking ‘mist’ and ‘mystery’.)” This makes perfect sense of course, except when it does not, which in itself is a very Monk-ish concept. Curtain call, picture Monk and his group exit the bandstand in a cloud of saw dust, headed to the bar for a night cap.

Of course one cannot talk about Misterioso without giving a tip of the hat to the cover art, which features a reproduction of Giorgio de Chirico’s 1915 painting The Seer. Surely the Italian surrealist didn’t foresee his work would make it on the cover of a jazz album (it was a tribute to French poet Arthur Rimbaud, and you can view the original at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City). But given the time, and location, that birthed Misterioso, it was a perfect choice, appealing to the Five Sport’s mostly bohemian clientele. That said, Misterioso was originally greeted with mixed reviews; with much criticism aimed at Griffin’s performance. For example, in his review for Hi Fi Review magazine, Jazz critic Nat Hentoff found that it was not one of the pianist's best albums, reprimanding it for “too little space for Monk's soloing and somewhat too much” for Griffin, whose saxophone cry and timing were more impressive than his solos.

Well, you know what they say about opinions. While Griffin is neither Coltrane nor Charlie Rouse, his successor in Monk’s band, he may just be the perfect choice for this album. And if Hentoff’s review of Misterioso implies a degree of blandness, one might argue that more than 60 years after it was recorded, it provides not only a rare snapshot of a formative phase in Monk’s career, but it is our time capsule, inviting us back to that hot, humid summer night in August 1958, allowing us to not just poke our heads through the doors of the smoke-filled Five Spot Café, but to spend the night swaying to the contours of some of Monk’s best music, performed in an environment that inspired the pianist to play less introspectively and more vividly than in the traditional studio setting that makes up the vast majority of his records. Though Monk’s performance on Misterioso may not be the best of his long career and may not be entirely unique in its ability to bring you musical euphoria, if you give it a chance, Misterioso will grow on you, slowly but surely, and before you know it, it will undoubtedly be a frequent culprit, if not a favorite on your turntable.

DJ Pari is a Richmond, VA, based writer, editor and jazz vinyl aficionado. He also has a second life in the music business, with DJ performances on five continents and collaborations with legends from James Brown to the Impressions of Curtis Mayfield fame.